Understanding Executive Functions

Executive function is an umbrella term that is used in neuroscience to describe the neurological processes that are involved in mental control and self-regulation (DiTullio, 2018). Every task, action, process, or activity you engage with involves a unique set of skills; those skills are your executive functions, or EFs. As an adult, from planning a party to determining which restaurant to go to for dinner — or, taking the student perspective, from selecting a text on which to write a report to selecting your entrée from the lunch cafeteria line — all these processes involve executive functioning. EFs at their most basic level are a set of mental skills. The Center on the Developing Child at Harvard University (2024a) defines executive functions as “the mental processes that enable us to plan, focus attention, remember instructions, and juggle multiple tasks successfully.” These processes are critical to how humans act and interact with one another, as well as how they engage in the world, tackle problems, and simply approach daily living. In education, it is used to describe a student’s ability to consciously control his/her thoughts, emotions, and actions so that goals can be achieved.

One common analogy for how to understand EFs is to think about them as being like the brain’s air traffic control system. In the world of air travel, air traffic control is critical to the success of being able to transport a person or object from Place A to Place B. Air traffic controllers oversee and direct every plane on countless sets of very busy runways. From small charter planes to large aircraft, the air traffic controller ensures that each plane is on the right track to arrive and depart at the exact predetermined time without interfering with other flight plans. Without this vital job, confusion and devastation would most certainly ensue. The body’s brain operates executive functions to act just like an air traffic control system. The functions are helping the brain — and by extension, the body — determine priorities, sort through information, and make appropriate decisions based on the information it has. These skills have been found to be independent of intelligence and can pop up as being problematic for all sorts of students (Reynolds & Horton, 2014). Because the human brain is not fully developed at birth, children are not born with these skills, but they do have the potential to develop them.

The Two Core Strands of Executive Function

As any parent of a newborn knows, no child has ever been born into this world with the ability to inhibit his/her impulses, form goals, and develop plans to meet those goals, all while having the wherewithal to follow through with the plan. Indeed, babies are completely reactive to their new surroundings and external stimuli, having only the ability to cry to voice their displeasure. Thankfully, however, babies have the potential to direct and self-regulate their cognition and behavior, for without this trait, humans would likely cease to exist.

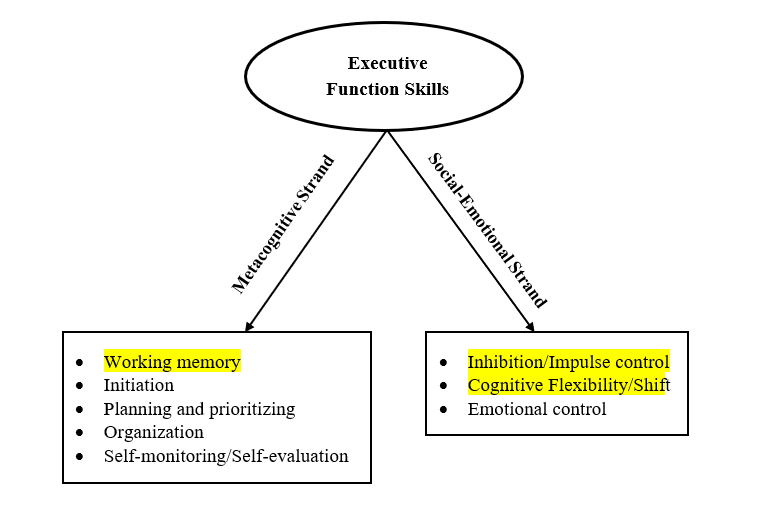

While this course is designed to explore only three executive functions (working memory, cognitive flexibility, and inhibition/impulse control), it is still important to address the fact that these three executive functions can be grouped into two core strands — the metacognitive strand and the social-emotional strand (Kaufman, 2010), with the prefrontal cortex controlling both strands.

The Metacognitive Strand

As its name suggests, the metacognitive strand is closely related to metacognition, or thinking about one’s thinking. The executive functions that are contained within this strand are responsible for the successful planning, starting, and completion of tasks. Not surprisingly, these elements are particularly important to academic success. When these skills are developed, students not only attend to important content (even if it is boring), but they do so purposely, meaning that they don’t waste a lot of time with unnecessary and extraneous stimuli. It is not just a matter of knowing the strategies to aid in this endeavor, but these executive functions — when developed — allow students to select and manage the strategies so that the information can be both understood and recalled later. Some sub-skills within this strand include such things as being able to set purposeful goals, initiate a required process for a specific task (as well as the steps within each task), gauge the quality of one’s progress, and manage one’s time and materials effectively and efficiently (Gioia et al., 2015). When combined, these executive functions allow students to purposefully initiate, regulate, and direct their learning.

The Social-Emotional Strand

Also known as SEL, social and emotional learning is a hot topic in education today. The Collaborative for Academic, Social, and Emotional Learning, or CASEL, is a worldwide organization devoted to using its resources to promote the integration of students’ academic, social, and emotional needs from preschool through twelfth grade. According to CASEL’s website, SEL is:

“the process through which all young people and adults acquire and apply the knowledge, skills, and attitudes to develop healthy identities, manage emotions and achieve personal and collective goals, feel and show empathy for others, establish and maintain supportive relationships, and make responsible and caring decisions.” (CASEL, 2024)

SEL is based on the premise that the best learning takes place when students engage in supportive relationships which then makes learning challenging, engaging, and meaningful. More and more, schools have a vested interest in SEL, as many of their curriculum choices and school/district-wide practices and policies are embedded in the successful implementation of this concept. Since SEL showcases how students and adults relate to one another across many different levels of the school system, it has proven to be an invaluable component of a positive classroom and school-wide community.

The prefrontal cortex of the brain acts as a sort of “command center” for executive functioning. Like its metacognitive counterpart, the social-emotional strand is also dependent upon executive functions. For a child to feel whole, competent, and connected, his/her social-emotional skills need to function in tandem with his/her executive functions, with executive functioning serving as the foundation. Building students’ executive functions and SEL skills together improves their chances of succeeding academically, behaviorally, socially, and emotionally. Some sub-skills within this strand include inhibition/impulse control, cognitive flexibility (a/k/a shift so that one can appropriately respond to a situation), and emotional control. This course is designed to take a deeper dive into three key executive skills that comprise both the metacognitive strand and the social-emotional strand.

Three Core Dimensions of Executive Function

The scientific world has a general, agreed-upon definition of executive functions, as already explored above. The field of education has, however, very specifically identified and agreed upon three dimensions of executive function skills, as described below.

- Working Memory. This is the brain’s ability to possess and keep information for a short period of time. Working memory “provides a mental surface on which we can place important information so that it is ready to use in the course of our everyday lives” (Center on the Developing Child at Harvard University , 2011). Because working memory is such an intricate piece of the executive function puzzle, it will be explored in greater depth in the next section as well as throughout the rest of this course.

- Cognitive Flexibility. Also known as shift, this is the brain’s ability to pivot from one thought, activity, perspective, or priority to another. This includes our capacity to use different behaviors in different scenarios. For example, while swinging from the monkey bars is completely appropriate for recess, it is not appropriate to climb on classroom furniture in the same way. In addition, cognitive flexibility allows people to apply rules to certain scenarios, such as it being inappropriate to treat the classroom like a playground. Because cognitive flexibility is another important and intricate piece of the executive function puzzle, it will be explored in greater depth in the next section as well as throughout the rest of this course.

- Inhibition/Impulse Control. The brain’s inhibition/impulse control consists of its ability to control and filter thoughts so that people can process and respond with appropriate words and actions. It includes the ability to focus, prioritize, select, or pay close attention to specific thoughts or activities. Because inhibition/impulse control is the third and final intricate piece to the executive function puzzle, it will be explored in greater depth in the next section as well as throughout the rest of this course.

In most situations, the brain relies upon these three functions to work together, rather than separately, so they are highly connected. When combined, these core executive functions are those advanced elements of cognition that allow students to stop and think before rushing to answer a test question, arrive at a solution, or simply respond to a statement or question from the teacher. It is for this reason that executive function skills are strongly related to school performance. Why? Because these skills are essential for managing academic demands, prioritizing tasks, allotting time to complete assignments, checking one’s work, following through on what was begun, and appropriately responding to a variety of social and stressful situations. Oftentimes, students who have problems with their executive skills may seem unmotivated, lazy, and daydreamy. This is only the tip of the iceberg. While this is what may appear on the outside, underneath tells a completely different story.

Why are executive functions critical for learning?

The development of executive function skills begins at an early age. As you are beginning to learn, EFs are fundamental to a person’s ability to function as both a youth and further into adulthood. As stated previously, these skills are not innate, and infants are not naturally born with them. They can begin to be taught when children are as young as preschool, and they are further reinforced and practiced throughout the school-age experience. Each of the specific skill areas identified above — working memory, cognitive flexibility, and inhibition/impulse control — have a direct correlation to activities in the classroom, and thus are fundamental to the learning process overall.

To learn new content, for instance, students must be able to take in and store information in both their short-term and long-term memories. The ultimate goal of education is to help students learn new content and skills to prepare them for the future ahead. Therefore, students are presented with new content day in and day out, thereby causing them to rely heavily on their working memory to hold this information. Let’s consider a few simple examples of working memory in the classroom.

- Kindergarten students are introduced to a song outlining the days of the week.

- Second-grade students are learning place value to the hundreds place and are presented with a chant to help them recall ones, tens, and hundreds.

- Fifth-grade students craft research reports and read/store information to determine important facts to integrate into their reports.

- Middle school students need to follow multi-step directions to complete a science experiment.

- High school students hear an unfamiliar word in a foreign language classroom and attempt to repeat it later during the same lesson.

Cognitive flexibility plays an important role in learning as well, as students are called upon to transition from tasks and ideas throughout the school day. This can occur throughout the entire school day, or it can happen simply in a moment. For example, as students engage with mathematical content, they apply different rules based on what is presented. A two-step math problem requires the ability to move from the first component of the problem to the second while aiming to solve the problem overall. On a broader scale, this cognitive flexibility is in demand all day long as students move from subject area to subject area and even from teacher to teacher (or multiple adults as they engage with school personnel).

Perhaps one of the most important executive functions for learning in the classroom is inhibition/impulse control. A child’s ability to exercise self-control over both their body and their words is extremely important to their overall learning trajectory. A lack of inhibition often results in struggling to stay on task and/or suffering from distractions or disturbances. In some cases, impulsiveness can lead to behaviors that are inappropriate for the classroom which can then cause negative interactions with other students. For example, a student who lacks this ability may be bothered by another student and respond instinctively, either in anger or even with a physical response, such as a push or a shove.

Executive Dysfunction or Executive Functioning Disorder?

We have briefly explored what the core executive functions are, but what about executive dysfunction? You may have heard this term used at school or even used clinically. Executive dysfunction refers to any problems related to being able to successfully exercise one’s executive function skills. This may include, for example, a struggle to regularly plan, the inability to give proper attention to something or someone, to exercise and follow through with a particular skill or strategy, or to properly manage one’s time. It is important to note that this is not related to one’s effort or “smartness,” but rather, it is a direct result of the brain’s inability to successfully demonstrate these skills.

While scientists have not identified one individual cause for executive dysfunction, research demonstrates that it can be linked to a variety of conditions, including the fact that it can even be passed on genetically (Friedman et al., 2008; Freis et al., 2022). These conditions include, but are not limited to, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), depression, autism spectrum disorder (ASD), obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD), head injuries, and more. A student can be identified as having an executive functioning disorder through the special education assessment process or by a clinician at their doctor’s office using a variety of tests to gauge their level of executive function skills. It is equally important to note that additional conditions not explored above, such as dementia, brain tumors, epilepsy, or substance abuse can lead to struggles in this area for adults. If caused by some of these additional factors or conditions, medical treatment may be necessary. However, students struggling to simply practice or take additional time to develop executive function skills can be supported in the classroom through a variety of means that will continue to be unpacked throughout this course.

Executive Function and the Pandemic

During and after the global COVID-19 pandemic, educators and families saw an increase in terms of students who displayed a variety of executive function struggles. This became increasingly evident as students returned to in-person learning, as these EF struggles began to manifest in students’ ability to study, stay on task, complete tasks, and focus on academics in general. Before continuing, it should be said that this challenge to practice or strengthen these skills throughout the pandemic period was completely unrelated to medical or other conditions. Given the unique circumstances of the time, students were expected to learn in entirely new ways and settings and unfortunately, many of them failed to appropriately adapt.

How did the pandemic impact students’ executive functioning skills?

There are several reasons why students experienced an increase in EF challenges following the pandemic. Let’s examine some of these reasons below (Education Resources, 2024).

- Modified Routines for Learning. The simple act of walking into a physical space where the intention is to learn actually provides a signal to the brain that it is time to engage in learning. This signal was stripped away from all our students in 2020 as they exited their classrooms in March and didn’t reenter them for a year or possibly more. For kindergarten students at that time, they never had a chance to engage in this experience at all, as their educational careers began when they turned on a laptop and met their teachers through a computer screen. Learning routines were completely disrupted and students’ social supports were ripped away, causing this rupture to have a direct impact on all students. For some, the challenge to engage in a new way was harder than it was for others. For many, bedrooms and playrooms — once relegated to privacy and personal space — became classrooms, and students struggled with defining how and when to shut down other behaviors that were clearly not associated with learning in these rooms (i.e., playing video games, listening to music, chatting with friends on social media, etc.). Cognitive flexibility and inhibition/impulse control were directly challenged as well, as students were forced to pivot to these new routines. State-dependent memory (SDM) is a term that refers to a phenomenon observed by scientists where consistent structures and conditions lead to stronger memory retention (Education Resources, 2024). In essence, working memory, and the ability to retain memories in general, is stronger when regular and expected routines or conditions already exist. Given the events of 2020, it is evident that students did not get to experience the regular routine of attending class in their local school, forcing many students to stretch their executive functions to their limits.

- Changes in Task Protocols. Stop for a moment and jot down the first five classroom procedures that come to mind that you implement with your students. How many of these five were directly impacted by the events of the pandemic? It is likely that all of them changed, or at least were elongated, as a direct result of the pandemic. The specific processes that students are required to implement at school were drastically changed during and after this period. One key process is general task completion, which is already a challenge for students struggling with executive functioning skills. In the classroom, the procedure to turn in an assignment might be to drop a paper into a specific bin. In and of itself, this can be challenging for those who have executive function difficulties because it includes multiple steps: first, complete the assignment in its entirety, ensure a name has been recorded on the assignment, remember to turn it in on time, and physically turn it in to the correct location. Imagine how challenging this became for students as they were forced to turn in assignments online! Multiple steps were added to the process: download a resource, rename a file, complete all the normal pieces of the task but learn to type at the same time, save the file, find the right location to digitally “drop it,” and upload it correctly. As it stands, any “normal” student might struggle with these steps, especially if they are younger or not tech-savvy. As such, it could appear that many students had executive functioning struggles when in fact they were simply, well, struggling. And for those who truly had EF deficits, the act of task completion was brutal.

- General Anxiety and Stress. While students’ interactions with the virus were generally milder, they were far from immune, and many of them unfortunately witnessed terrifying and possibly traumatic events from the virus itself. The general fear that ensued, as well as the possibility of watching family members or caregivers suffer from the virus or even lose their lives, caused stress for everyone in the entire world, including our children, which ultimately led to increased levels of anxiety and depression. Needless to say, this had a huge impact on students’ executive functioning skills. Stress not only impedes a student’s ability to use their EF skills, but it also affects their general ability to develop and nurture them.

Most students (anywhere from kindergarten all the way through to seniors in high school) were directly impacted by some (or all) of these challenges during the pandemic. As every teacher knows, school is a critical place to not only guide students to academic understanding, but it is also a safe space to help students learn, practice, and develop their executive functions. As such, educators had, and continue to have, a critical role in supporting students in this area.

Connections to the Content Areas

Before we move on to unpack each of the three dimensions of executive functioning skills, let’s take a moment to picture how they might appear within the content areas and grade levels. The purpose of doing so is to keep this information in our own working memories as we move forward in our learning throughout the course.

| Executive Functioning Examples | ||

|---|---|---|

| Reading | Writing | Mathemathics |

| Kindergarten students holding multiple sounds for the letter “c” in their minds (working memory) | First-grade students learning text types and adjusting their response to the prompt (cognitive flexibility) | Second-grade students adding and subtracting within 20 using multiple strategies to do so (cognitive flexibility) |

| Fourth-grade students engaging in guided reading and whisper reading until called on (inhibition/impulse control) | Sixth-grade students practicing argument writing for the first time and selecting appropriate facts to demonstrate their writing (inhibition/impulse control) | Third-grade students recalling different order of operations to apply during mathematics (working memory) |

| Reading and memorizing lines for the school play in middle or high school (working memory) | Creating an outline for an upcoming research project in middle or high school (cognitive flexibility) | Being able to productively work through a multi-step proof in geometry while staying on task in middle or high school (inhibition/impulse control) |

Executive Function: The Key to Success

Executive function skills are necessary to successfully complete the everyday tasks that life throws your way. As any new parent can attest, children are not born with executive function skills, but rather they are learned over time and through explicit instruction. Oftentimes, teachers and parents wrongly assume that a student is simply not putting forth the effort needed to succeed. When this occurs, s/he may begin a downward spiral. As time goes on, this downward spiral continues, resulting in feelings of insecurity, anxiety, and anger. Even when academic interventions are begun, they are often inadequate because the issue of executive function is not specifically addressed. And it doesn’t stop there. Even as adults, people who struggle with their executive function skills can face serious challenges in meeting their goals and getting ahead in their chosen profession. As we delve further into the world of executive functioning, you will learn how working memory, cognitive flexibility, and inhibition control are all crucial to students’ success, both at school and throughout their lives.

Are you curious? Want to take a deep dive on this topic?

To learn more about leveraging executive best function practices, visit the course details page for Solving Core Executive Function Challenges (K-12) to view the topical outline and download the syllabus.

Ready to Enroll?

Choose your course option below. Within 24 business hours, you will receive an e-mail from PDI with access information and instructions for participating in your course.

If you still have questions, visit our FAQ page or contact PDI's Program Specialist, Melissa Breazeale for additional questions or clarification.

View PDI's Catalog of Courses

Check out a list of all PDI graduate-level online courses or sort by grade level or subject area.

Register Now!

Quick access to register for PDI's online courses using our secure system.

Learn More about PDI

Find out how to reach PDI and get answers to any questions you may have.

Access My Course

Access PDI's online learning management system to begin your course.